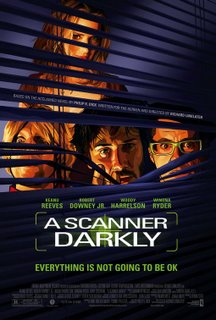

Review: A Scanner Darkly

There's a lovely transitory period in Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly in which it ceases being a non-starting, affable yuppie-stoner amalgam warning with an undercurrent of post-Watergate/post 9/11 paranoia, and becomes something else entirely. It becomes emotional. An undercover narc, Fred, removes his scramble suit (so-called because it conceals its wearer as a "vague blur" under the constantly shifting identity of millions), walks down the street, goes home, and becomes Bob Arctor (here played by Keanu Reeves) - the trashy, thrashy boyfriend of Donna Hawthorne (Winona Ryder), who's hooked on the super-drug Substance D and debates missing gears on eighteen-speed bicycles. Arctor lies down, the music swells, and little Keanu narrates his heart out. "What does a scanner see?", he muses, "Into the head? Down into the heart?". Up until this point the film has been as schizoid as its protagonist, ostensibly flitting between junked-up, cyclical stoner talk and cagey science-fiction, but here Linklater asserts his real rabble-rousing intentions. Dual personae compete and converge, and even as Reeves occasionally clunks his dialogue, and stirs and looks sour; something odd happens. We care.

There's a lovely transitory period in Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly in which it ceases being a non-starting, affable yuppie-stoner amalgam warning with an undercurrent of post-Watergate/post 9/11 paranoia, and becomes something else entirely. It becomes emotional. An undercover narc, Fred, removes his scramble suit (so-called because it conceals its wearer as a "vague blur" under the constantly shifting identity of millions), walks down the street, goes home, and becomes Bob Arctor (here played by Keanu Reeves) - the trashy, thrashy boyfriend of Donna Hawthorne (Winona Ryder), who's hooked on the super-drug Substance D and debates missing gears on eighteen-speed bicycles. Arctor lies down, the music swells, and little Keanu narrates his heart out. "What does a scanner see?", he muses, "Into the head? Down into the heart?". Up until this point the film has been as schizoid as its protagonist, ostensibly flitting between junked-up, cyclical stoner talk and cagey science-fiction, but here Linklater asserts his real rabble-rousing intentions. Dual personae compete and converge, and even as Reeves occasionally clunks his dialogue, and stirs and looks sour; something odd happens. We care.Everything points to A Scanner Darkly being another of Linklater's cheeky, well-written escapist fantasies. The damn thing is rotoscoped. It plays with genre expectations initially in this manner, but quickly Linklater is unafraid to make deliberate and literal character insinuations, given the medium's, and this particular breed of animation's, advantages. So, yes, come closing credits we have a couple of fittingly obvious plot points and an ending to satisfy that nagging narrative, and yet it also reaches a poignance of sorts, augmented by a snippet of the author's coda. For some this may prove sentimentally unwarranted and cack-handed, but at worst it's oafishly cine-literate and at best emotionally transcendent. Reeves is actually called upon to emote and more than partially succeeds, Robert Downey Jr. balances delirium with insanity, and Winona Ryder, still her bug-eyed and charming self, brings a surprisingly welcome messy emotional depth and availability to a character as complex but potentially alienating as Donna.

Just as Before Sunset excised the blithe, giddy enthusiasm of Before Sunrise in place of reasoned maturity nine years later (whilst losing none of the original's happy lyricism) so, too, does Scanner transpose the philosophical naiveté of Linklater's previously drug-addled users of Slacker and Dazed and Confused with adult consequence in a fictitious police state "seven years from now". Of course it helps when your source material is Philip K. Dick, a pond Hollywood has been gladly dipping its feet in since 1982's Blade Runner through to 2003's Paycheck, only this time with less of the whizz-bang and more of the whimsy. In fact, the novel is so fiercely personal and so far removed for the author's self-professed earlier "ray-gun phase" it seems fitting that Linklater, a director known for talk rather than action, should graft a tale of innate human self-destruction and tragedy; even if he fumbles with a none-too-sly masking of conspiracy and awry sub-plot.

The film and novel may suffer from the same curse and blessing -the plot is consciously languid and intermittently off-the-boil, Arctor's real 'motivation' for drug abuse isn't apparent until near-conclusion- but overwhelmingly Linklater focuses on the folly of self-induced arrested development and the perpetual childishness of narcotics over hollower, mainstream machinations. It's not as grim as, say, Requiem for a Dream but is just as intellectually and gut-crunchingly viable, if a little vegetative for its own good at times. Eye-candy for nose-candy is a wonderful thing, and if A Scanner Darkly is guilty of any cliché, it would be only be the eternal message of any drug movie: snort carefully.